How to quality assure

2021-10-04

Chapter 1 Introduction

Whenever we produce a new model or a new piece of analysis, it is important to quality assure (QA) our work. This allows us to check that our analysis is credible and provides assurance to senior leaders that modelling risks are being managed appropriately.

The principles of good QA are outlined in the DfE QA framework (which can be found here). The QA framework sets out a list of rules that one must abide by when QAing a piece of work, yet provides very few examples.

The purpose of this documentation is to provide extra examples that support the QA framework. It is important to ensure not just that our work is QA’d, but that it is QA’d well. The aim of this documentation is to provide guidance on how to ensure that the QA being carried out is being done properly in order to provide an accurate picture of the reliability of analysis. It is aimed at both quality assurers (teaching a QAer how to properly QA a piece of work) and at original code/model authors (teaching an analyst best practice that will allow a piece of work to be QA’d easily).

By necessity, this guidance isn’t comprehensive. QA takes different forms depending on the work that is being carried out. If you are still unsure on how to carry out good QA in your area, contact your QA officer).

Before discussing ‘good’ QA, it is useful to think about what it means for QA to be ‘bad’.

1.1 What does ‘bad’ QA look like?

There are many examples where QA is not up to scratch despite following the QA guidance. Here are a few of these examples:

The QA is rushed at the last minute. This could be due to the urgency of the project, or pressure from senior leaders or clients, but this can lead to mistakes in the QA or ‘cutting corners’. Always ensure that an appropriate amount of time is allocated for QA. This amount of time will often depend on the scale of the project, and the type of analysis that is done.

Parts of the analysis are assumed to be ‘right’. Even if results look correct, it is important to properly check the analysis that has been done. Just because something looks ‘right’ doesn’t mean that it is!

The QAer doesn’t ask any ‘real’ questions about why things have been done the way they were.

- If a QAer says ‘everything is perfect’ and raises no concerns or doesn’t ask any questions at all, this may suggest that they haven’t actually undertaken robust QA.

- Similarly, if someone says that they understand something very complex the first time around, they probably don’t understand it. This may be a case of the work being too complex that they struggle to put into words exactly what they don’t understand. It may be worth explaining complex pieces of work a couple of times anyway, to ensure that everything has been properly understood.

- Asking questions can build understanding, and we encourage all QAers to ask questions (even very simple ones!)

Assuming that things are right because the ‘data’ or ‘the software’ says so. Always avoid a ‘computer says yes’ attitude. Just because a computer doesn’t pick up on any errors doesn’t mean that the analysis is completely free from mistakes!

QAers being afraid or nervous about raising concerns. This may be more of a problem when QAing for senior analysts. QA is a vital part of every project, and QAers should be made to feel that they are able to voice concerns whenever they arise. It is important to talk through each of these concerns rather that simply disregarding them.

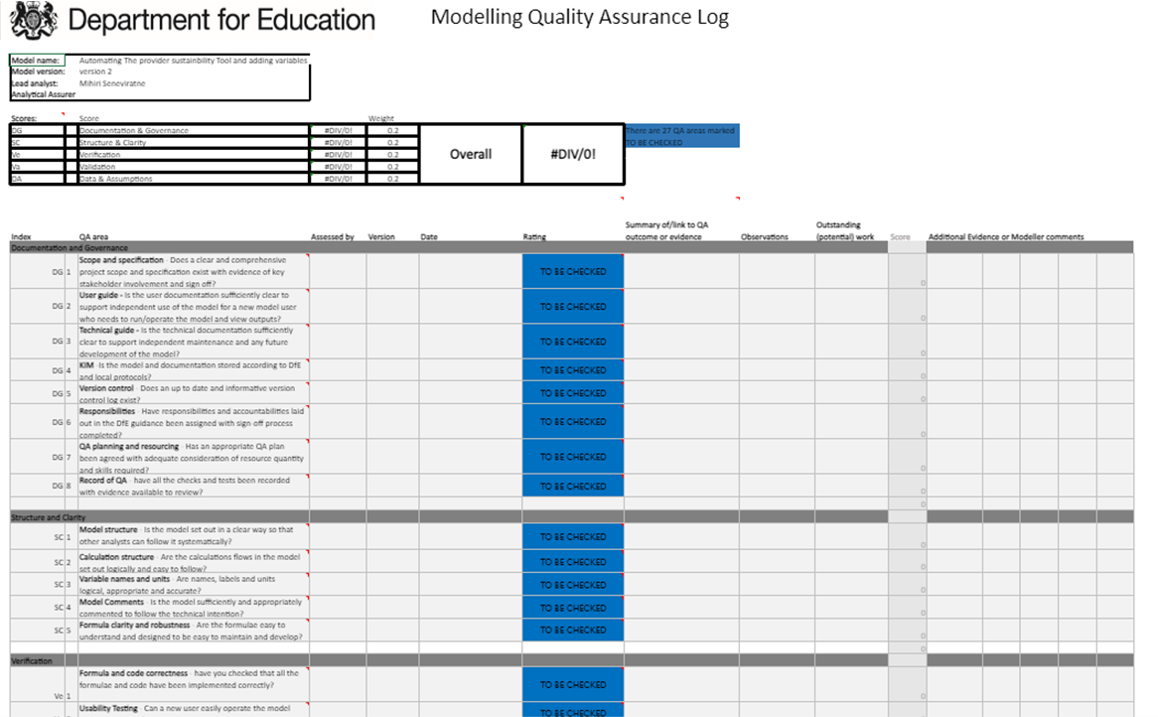

Confusion around what QA is needed and what QA has been done. This will be addressed within this document. An up-to-date QA log should be kept at all times to assist with keeping track of QA that has been done, and help highlight where QA is still required. A QA log template is available on the DfE Quality Assurance page

1.2 What can happen without sufficient QA

In this section, we briefly discuss two examples of where QA wasn’t implemented properly, and the effect that this had.

- The InterCity West Coast Rail franchise

In 2012, a franchise competition to see who would continue to run the InterCity West Coast Rail franchise was set up by DfT. However, DfT made fundamental errors in the way it calculated risks for each big. Real and inflated financial figures were mixed up and the spreadsheet contained elements of double counting. This resulted in an unsuitable company being chosen for the franchise.

When faced with accusations from Virgin Trains, who had expected to win the franchise, DfT assured them that their maths was correct. However, when legal action was launched, a more thorough check was conducted, which brought to light the significant errors and cost £8.9m.

As a result of this, £40m was reimbursed to bidding companies and 3 civil servants were suspended. Altogether, this cost the taxpayer almost £50m.

“Significant risk issues were identified through internal and external quality assurance procedures over the course of the ICWC franchise process” - House of Commons Liaison Committee.

You can read a news article about the InterCity West Coast Rail franchise here, and find a Lessons Learned document published by the NAO here.

- The Teacher Pay Grant Project

Following the publication of the 2018/19 Teacher Pay Grant, DfE quickly discovered that the published allocations were incorrect. 4 year olds had been double counted in the data due to inclusion in both early years and school datasets. This resulted in almost 9,000 schools being allocated a different amount of money than they should have been, and cost roughly £1.1m.

The team had QA in place, but there was still an issue here. Policy kept changing, means that the team had to move quickly and rush to use new data without speaking to experts. When the work changed, they should have gone back to the QA plan and updated it. More time should have been made to allow for sense checks and to allow the team to get a better understanding of the dataset. A combination of significant time pressure and rapidly changing scope led to the team cutting corners, which resulted in these mistakes being made.

You can read a news article about the Teacher Pay Grant project here.

1.3 What does QA involve?

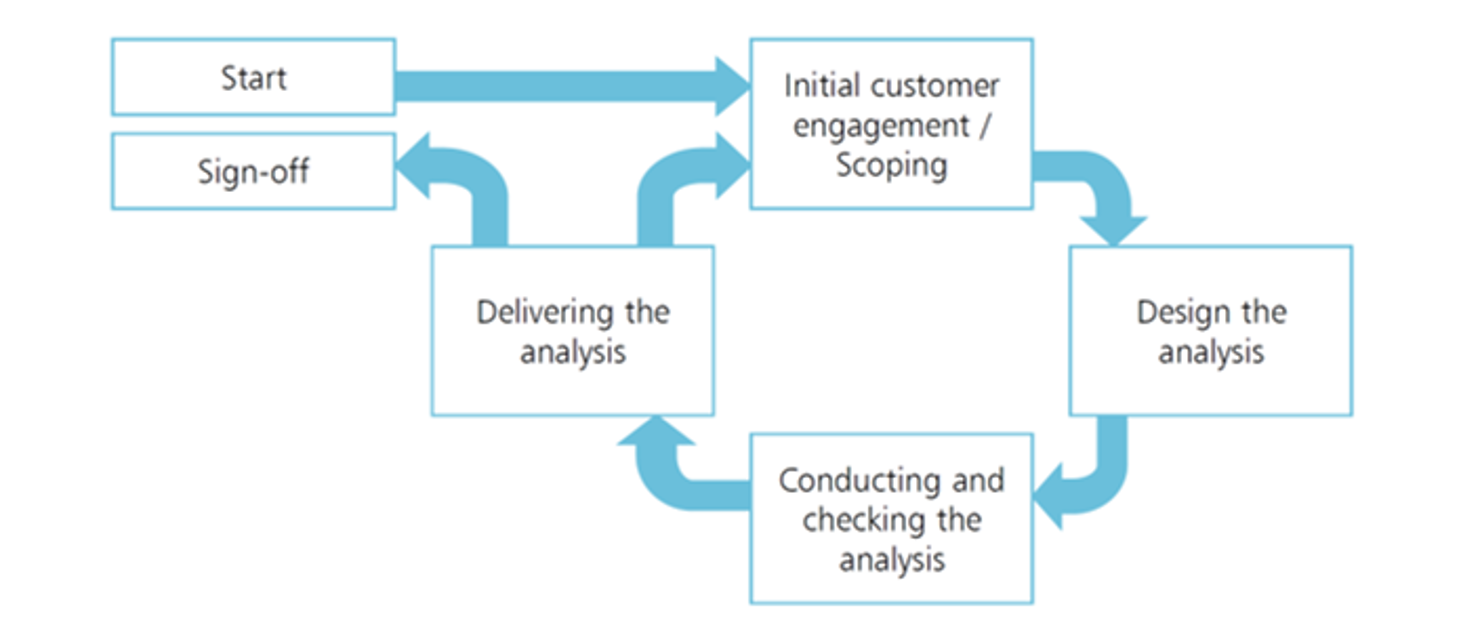

Here is a chronological list of tasks and activities that should be carried out during a project cycle:

Assemble a QA plan and consider how the work will be QA’d. A template for the QA plan is available here. The QA plan should cover roles and responsibilities, as well as plans for specific activities and documentation. At this stage, it is important to think about who will be doing the QA, and how the work can be QA’d properly.

Ensure you are doing the right work. Make sure you are on the same page as the commissioners of the project, and be clear on what questions you are trying to ensure. Question the methodology to make sure you are taking the correct steps. A list of the questions you may wish to ask are given in Chapter 2.

Do the work, and self-QA as you go along. Self-QAing your work will help others to QA your work later on (see Chapter 3). If you are writing code, ensure that you maintain coding standards (see Chapter 4).

Have the work QA’d by someone else (see Chapter 5). Make sure you’ve taken all the correct steps to make the QA process as smooth and straightforward as possible. Arrange a meeting to discuss your work with the QAer and make time to answer any questions they may have.

Summarise QA and request analytical assurance (if appropriate).

Repeat! Every time you go around the analytical cycle, QA must be carried out!

The Analytical Cycle, taken from The Aqua Book (HMT, 2015)