Chapter 2 Introduction

2.1 Background

Version control is an important part of any project. It allows you to respond reactively to requests for changes, ensure that you can easily reproduce an earlier iteration and provides an audit trail of what work has been done and the decisions that have been made.

Most people would recognise this and probably are doing some form of their own version control to ensure they are able to respond, albeit not immediately, to these situations.

As analytical functions move away from software such as Excel, SPSS, etc. towards fully code-based solutions using languages such as R, Python, SQL, etc. there is a wealth of pre-established expertise that can be lifted from traditional software development practices.

Git is widely used software for ensuring version control is done in a standardised manner and there are a wealth of applications that allow you easily to adapt its use to your needs.

2.2 Manual Version Control

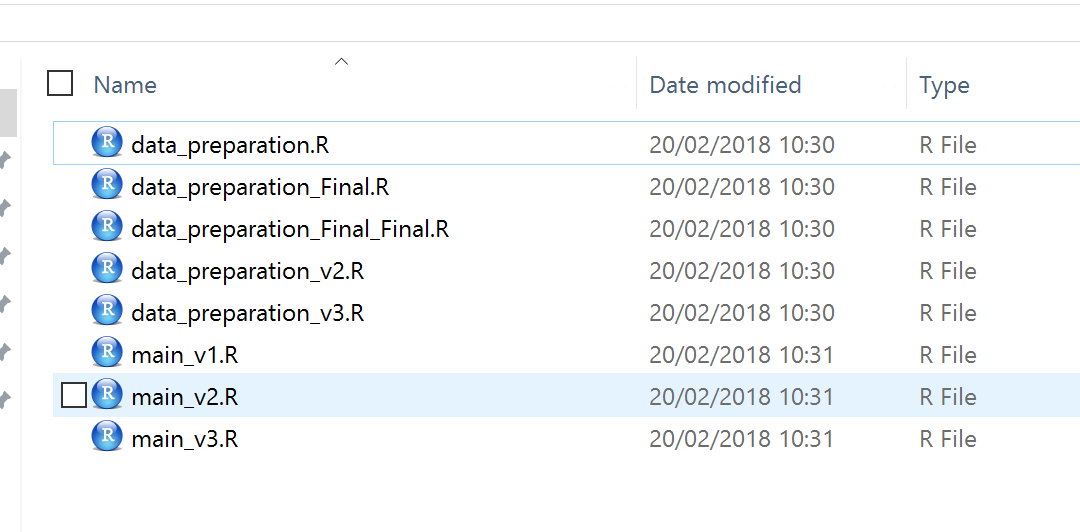

Any book illustrating the usefulness of Git will start with an example similar to the following.

This approach creates versioned files using suffixes with some sort of convention. This can work if you have a small number of iterations but the following questions need to be answered:

Which is the final version?! - Despite attempts to use standard naming conventions, you will inevitably reach a stage when you think you have a ‘final’ version, and then another change will come and your previous convention will be broken.

What files actually constitute this analysis? - Folder structure changes over time. Scripts merge, are broken down into subscripts and files that may no longer be needed could be sitting in your folder. For a colleague quality assuring your work or anyone (including yourself) picking this up in the future, this structure is not going to help you as it will be unclear what is really needed.

What are the differences between these versions? - Although these versions have different numbers we can’t easily tell what the difference between them are and would have to manually compare differences to see what’s going on. There is no indication that these are linked to specific items of work.

How do you collaborate using this structure? - Collaborating using this sort of versioning means you are going to have to introduce others to this structure and/or manage the process of adding pieces of code, likely passed across via email. Keeping track of this adds to the challenge.

The main take home points from this is that there are lots of challenges that come with this, and these challenges can take away from the task at hand. The bigger your project grows, the more challenging this will be.

2.3 Git

Git is the widely used version control system for code development in the world today.

It is command line software, language agnostic and at its root, just looks at differences between plain text files.

At its most basic level Git allows the following:

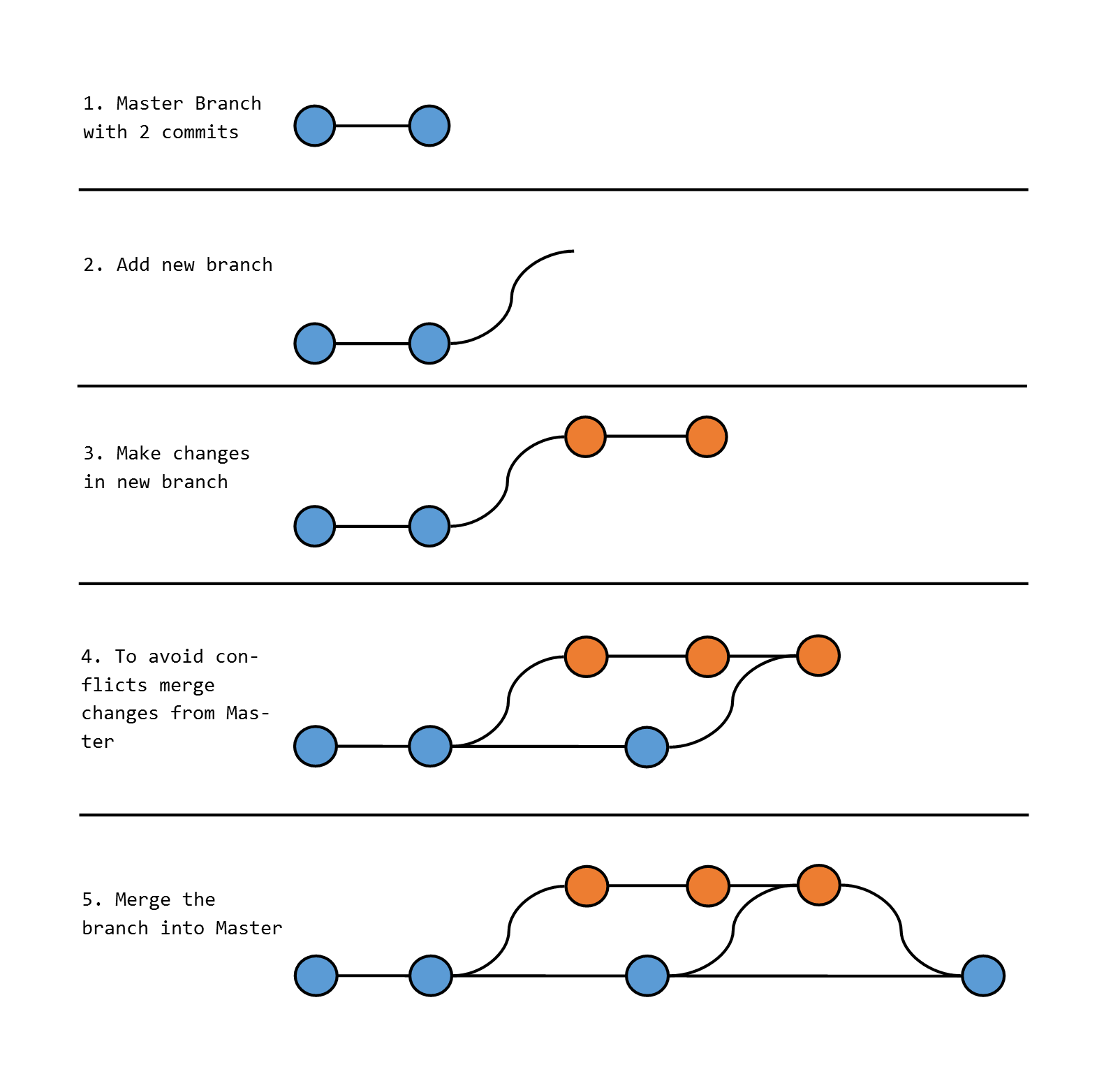

Commits - Create checkpoints in your code development process that you can go back to if required.

Branch - Create exact replicas of your project folder in which you can try out particular ideas without editing the main version.

Merge - Systematically merge these changes back into the main version of the code.

Git has the ability to check the differences between 2 versions. This is invaluable information and means that rather than checking the whole project code at an undetermined time in a project the task becomes:

What changed since the last working version, was that done right and does that change impact anywhere else?

Note: Git is command line software but many development environments (including RStudio) provide the functionality via the graphical user interface.

2.4 Collaboration

So far we have only looked at local version control. This is great for yourself to go back to previous versions of your work but doesn’t really offer a solution to collaborative coding.

What is needed is a visual platform where central versions of the code can be stored with the following functionality:

Users can take copies of the code on their local machine.

Users can make changes to the code locally and submit those changes for review.

The review process can be managed and if any changes are required they can be made in a systemised manner.

You can think of these sort of systems as wrappers for Git, where merges into the main version of the code are safeguarded.

One of the most well known systems for this is GitHub. GitHub is popular with open source projects because it provides good functionality for sharing code publicly. Additionally, some companies pay for business accounts.

For the purposes of this book we look at using Azure DevOps. This common tool for enterprise for software development provides us a secure set-up which integrates well with our Windows (AAD) log ins. As such, this should be our collaboration tool of choice for private work. If you are undertaking work which could/should be public, you may wish to consider using GitHub.

Git, GitHub and Azure DevOps (a.k.a. Git is not GitHub)

A common source of confusion is the assumption that Git and GitHub are somehow the same. They are not - although the confusion is understandable given the shared naming.

Git is version control software. It can either be used to manage code locally on a single machine or, much more commonly, to communicate with and manage code on a remote repository. (Other version control software exists, but is not used within DfE)

GitHub is a remote repository and code collaboration tool. It can be communicated with via Git to act as a central code store for a project.

Azure DevOps is a remote repository and code collaboration tool. It can be communicated with via Git to act as a central code store for a project.

Put another way, Azure DevOps and GitHub do the same job. Git does a different job, and can interact with either of them. In DfE, we use the combination of Git and Azure DevOps by default, although Git and GitHub will sometimes be used where appropriate.

The most important difference between Azure DevOps and Github is that the former is hosted on a private DfE server and access can be controlled; the latter is hosted on public servers and, by default, code hosted there is publically available.

2.5 Azure DevOps

Azure DevOps (DevOps) is a code collaboration tool for managing projects consisting of multiple developers.

DevOps is code agnostic. Although not aimed at R directly, it does provide the functionality to manage any Git-controlled project effectively.

On top of this, it provides project management functionality that, when coupled with a Git workflow, encourages well planned and executed projects, where each commit is a specific item of work. This functionality is optional but is encouraged.